Michael Huddleston

“He just seemed impregnable. If there is an end that’s inevitable, be honest about it and discuss it.”

Michael Huddleston lives with a heart condition that’s possibly the same one that killed his father when Michael was only fifteen. Now a father of two, he’s determined to have more time with his own children than his dad did with him.

Michael Huddleston’s pacemaker is introduced before our interview even starts. But it’s important for context. Vital, even. Visible even through his shirt, under the skin above his left breast, is a rectangular-shaped object.

“That’s not a packet of cigarettes, that’s my pacemaker-slash-defibrillator,” he says by way of explanation. He’s likely made the joke many times, but it works. “You’ll understand this if you play video games, but your defibrillator is like an extra life. If your heart stops and you go into cardiac arrest with one of these in, it can jolt your heart back to beating.”

And Michael’s heart certainly could stop – that’s what happened to his father, Keith, too early for him to have had such a lifesaver inserted into his chest.

“I came home one day from school when I was fourteen, I think, so in 1981, and Dad plonked a current affairs magazine down on the table in front of me. He said, ‘What’s this thing?’ and pointed to the cover illustration. I looked at this strange-looking contraption. ‘No idea’, I replied.

“He said, ‘If they had invented this type of pacemaker last year, I wouldn't be dying’, and I went, ‘Right, so are you dying?’”

Michael knew his father wasn’t well – the family had moved from Masterton to Wellington ostensibly to be near a good cardiac unit, and Michael had spent many hours mostly waiting outside hospitals in the car, listening to music rather than visiting his dad. But – dying?

Michael also knew his dad wasn’t the dad he’d once been – the dad he “did heaps with”, all sorts of sports with, followed around like his biggest fan (he was), and did his best to do everything his dad did.

“Dad had been my hero,” says Michael, with a crack in his voice. “But as he got sick, he just got so grumpy and difficult to spend time with because, I think, he was really frustrated he could no longer do the things he once easily did. I know now exactly why he was that grumpy, because I felt much out of gas before I got my pacemaker.

“The pacemaker’s made an enormous difference to my life. My father died when he was fifty and I’ve made it to fifty-seven, but I've needed this thing over the last three or four years. I'm pretty sure I would have died without it by now, so I'm kind of living on stolen time from my father in a funny way.”

The pacemaker keeps Michael’s heart at a steady sixty beats per minute. As his father’s medical records are lost in time, there’s no way of confirming a congenital factor. Michael knows his dad had a type of arrhythmia while he has atrial fibrillation, so their symptoms rhyme at least.

Michael’s heart symptoms started after he went on a strict diet and started doing heaps of exercise when he was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. His niggling symptoms, tiredness mostly, became more acute in 2020 when his family (his wife and twin daughters) took “a catastrophic trip” up Mt Ruapehu.

“Turned out I was in heart failure, which is when your blood's not pumping well enough around your body. The blood had settled in my feet, so I had oedema, and still have oedema in my extremities. We were up the mountain skiing and I couldn’t put on my ski boots, which were fitted to my feet. I just couldn't get my feet in them and I felt terrible. I ended up having eight kilos of liquid down in my feet.

“But I didn’t think it was my heart. I thought I had something wrong with my kidneys, because there was so much liquid in my feet. They looked ridiculous, like a cartoon. I went to my GP. He recommended a cardiologist. I went to the cardiologist. I found out I was in heart failure. We tried to solve it with medication, but in 2022 he called time on that and decided to go for a device.”

That “extra life” device was installed in April 2022.

“What was happening was that my heart rate was very slow, and the atrial fibrillation means there's a false beat, so while it's doing thirty beats per minute, some of those are only a partial beat, not a full beat, so I wasn’t getting enough oxygen around my body. I felt like I had no gas in the tank the whole time. I’d go out intending to have a long walk, but I’d make it only around the block, come home, go upstairs and go to bed,” he says, which is not great for a man who loves being an active father to two young daughters.

“That's exactly like my dad was. He would come home from work and be exhausted. He'd go straight to bed. Certainly, my irritability echoed his.”

I’ve known Michael for quite a number of years, from when we worked for the same television production company. Then he was a documentary and unscripted TV director, but the slowdown of the television market, as well as the slowdown of his health, means he’s spent a lot of time being mostly dad to his daughters. He loves music, and his Wellington home has a comfy listening corner for his collection of vinyl. He’s recently taken up bridge, and has a monthly poker game with a group of guys who’ve been bluffing and raising each other for getting on twenty years.

“It’s more like a men's group or a support group. The gambling is part of it, but it's only a very small part. It's more about socialising, and we try to outdo each other in terms of catering.”

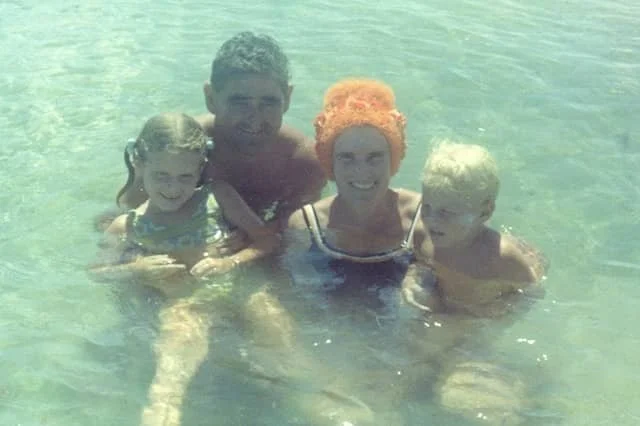

Michael was born in Fiji, where his parents were teachers. They moved back to New Zealand, to Masterton, at the end of 1972, which was a huge culture-and-temperature shock for a young boy unused to wearing shoes. Then, when Michael was twelve, the family – Michael’s mum and dad, and his sister, three years older – moved to Wellington. Keith had just been diagnosed with a significant heart condition so being close to a major hospital was wise.

“This was about when my father was becoming increasingly irritable, and my relationship with him changed substantially as he became ill. I worshiped him. He played a lot of sports, and if he went out for a jog, I would jog behind him. If he went to play squash, I would play squash in the court next door, and sometimes I could play with him. If he went out to play golf, I would do whatever I could behind him. But he ran out of energy to do that sort of stuff, and he ran out of patience to be as good a father as he had been.”

Add to that the usual abrasions of the teenager-parent relationship, and some resentment at being moved away from his friends without much more explanation than, “Dad is sick, we have to do this”. Michael saw that made sense, but he’d been happy in Masterton.

“Our relationship continued to diminish from the time we moved to Wellington to the time he died. I didn’t understand how his illness made him act the way he did. Part of me thought he didn’t like me very much. We just didn’t get on well anymore. I would hardly ever go and see him in the hospital, although sometimes I’d relent and come in if Mum said he wanted to see me.

“Now I know he was extremely unwell and probably doing the best he could. But I was losing admiration for him, and that’s the worst thing.” Michael looks crushed. It’s the ideal time for his very insistent cat Zorro to meow loudly for entrance. We use the distraction to gather ourselves.

Leading up to his father’s death, Michael experienced a number of alarming incidents. Keith’s skin had become extremely thin, and he bled very easily.

“I remember coming home from school once and it looked like there'd been a murder in the house. There was blood all the way up the staircase, and blood down the corridor towards his room. Also, I think he had maybe eight heart attacks before he died? That's eight instances of heart attacks where he’d be taken away from home, or school, from his teaching job, in an ambulance.

“Those sorts of things happened so often that, while I knew he was obviously really sick, I don't think I'd rationalised that he was actually going to die soon, that one of these attacks was going to get him one day. He seemed to be impervious to them affecting him. He’d go to hospital and he would come home, like the Black Knight in “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” repeating, ‘Tis but a scratch’ and carrying on fighting.”

The day Keith died, Boxing Day 1983, he’d been sitting at the table doing some algebra, which he did for fun. “He was a very, very bright mathematician,” says Michael. “Friends of mine were having a post-Christmas party and I went along. But I just wasn’t…” Michael breaks off, thinking back, remembering.

“I was at this party. I’d been there for only three quarters of an hour or something and then I had a sudden feeling… I was within walking distance from my house, it was just a school field and a couple of streets away. I thought, ‘I don't want to be at this party. It doesn't feel right’, so I left. As I got to the school field, I looked up at our house and there was an ambulance. I raced to the house and upstairs to the kitchen, which was right next to where I’d left Dad doing his algebra.” Michael’s speech slows down…

“I found people working on my father, trying to keep him alive. He was still conscious… I think my mother said to me, ‘Go talk to your father’. I did… And he said to me… ‘I've been a shit to you’....”

It’s very hard for Michael to talk. His throat is closing. So is mine.

“And I said, ‘No, you haven't…’ And, yeah, he just died. I would have been home for maybe two minutes.”

Michael’s not a premonition kind of guy. He doesn’t think it was a premonition, that compulsion to come home. Me, I am a premonition kind of gal, and I’m going with premonition.

“Rationally, I don't believe in it, but I’m very glad he had a chance to say that to me, and that I had the chance to say no, because then I knew he wasn't a shit. After that, of course, my own health issues spelled that out for me.”

He’s told this story a few times to people, he says, including his wife, and reckons he’s more emotional now than he usually is retelling it. But it’s rather an emotional story. His sister was there, too, he says, so they were all present when Keith died. He’s never talked to her about her memory of it, “although I probably should”, he says.

“I have almost no memory of anything that happened after Dad died. I have that strong recollection of his final minutes, but I've kind of blanked the rest of it out.” He does remember that the celebrant who took his father’s funeral service just before the New Year, included some religious material in the service, after being strictly told not to.

“I remember being resentful that the religious stuff made it into the funeral, because my father was agnostic and he wouldn't have been down with that at all. I felt he hadn't been represented particularly well at his funeral, and I feel a little bit bad about that.”

Largely, Michael didn’t feel left out of the funeral proceedings, nor did he feel particularly engaged. The only negative thing came much later, he says, when he tried to find his father’s cremation plaque and couldn’t. He eventually located it, and wasn’t impressed.

“I was disappointed. What is left of this man if he's just a tiny little plaque? So, subsequently, when Mum died my sister and I decided to have her ashes interred in Karori Cemetery, and the plaque we put there acknowledged my father as well. I think I've had one failed visit to Kapiti, then the visit where I did actually find the plaque, but that's as much as I've done to visit my father to remember him.

“Whereas the one where he and Mum are remembered in Karori, I include that on my walks. I walk over there and visit that site about six times a year. At one time it was probably once a month. My sister goes there every year on the day of our mother’s death, and quite often she reaches out to me, and I'll meet her there. It’s nice having somewhere like that to return to, and it’s great if it can be part of your routine.”

Michael remembers some adult support around his father’s death, saying he’s always been close to his mother’s brother in Dunedin, who came up for the funeral. “The teenager part of me was kind of, ‘Oh, this is awkward talking to these boring adults’, but I was close to that uncle, who is still alive.”

A good school friend lived nearby, and the summer Michael’s father died he was welcome at this friend’s house whenever he needed to get away. “Grant had a really kind mother – my mother was kind, too, but it’s good to have somewhere to go. There's nothing less cool than having a dead father and a mother who's struggling, and my sister was getting ready to leave home for university so there was a lot of stress in our house. It was good to have an escape.

“But my friends, were they supportive…? Fifteen-year-old boys…? I imagine a fifteen-year-old boy now would get a lot more empathy than I had back then. But I didn't expect anything.”

Michael reckons his behaviour changed after his father died. “I'd been a pretty straight kid until that point, but I started hanging out with a different sort of person in high school the following year. My father had been a big smoker before he got sick, and he’d been drinker, too. As he got sick, he let us know that cigarettes and alcohol are not great things.

“I hated all of that stuff, alcohol and cigarettes, but I started experimenting with dope a bit, and I had some friends who were kind of stoner types. I don't think that would have gone down at all well if my father was still around. I don’t know if I would have even done it if he’d been alive? I can’t be sure.

“I had experiences following his death that I wouldn't have had, probably, if he'd been alive, but I don't regret those. I didn't have any fall from grace as a result of it. I think it probably widened my worldview slightly, too, from being, you know, a bit of a square to not-such-a-square.

“And when I was with my dope-smoking friends I could just check out, you know? I didn't have to face up to everything else. I didn't have to think about serious stuff. They all knew what had happened to Dad, and when they had the munchies they’d all come around to my house and Mum would give us food. They all liked my mother. I think Mum was a bit worried about me during that period, but none of it damaged our relationship.”

In turn, Michael was worried about his mother, giving him more motivation to “check out”, he says. She’d had a mastectomy and significant radiation treatment when Michael was about ten, and now her breast cancer was back the year after his father had died. Michael worried about losing his remaining parent. “I definitely thought that was on the cards. I remember thinking, ‘I'm doomed’, or ‘We're just cursed with very bad luck’.” His mum recovered and lived until 2016.

His “druggie phase”, and those feelings of being cursed, dissipated by the time Michael reached university, choosing to stay close, going to Victoria University in Wellington. That was a wee bit about staying close to his mother, he says, because his sister was away in Auckland, but it was also convenient. And cheaper.

Rather than focusing on mathematics, as he might’ve had his dad still been around, Michael veered towards newer interests. “I was always good at mathematics, and I did do stage one mathematics, but then I gave that up as I was more interested in English literature and drama. Partly because, with Dad’s death and Mum’s cancer, a fatalism crept into my head, I think. I made the decision that when I’m going to uni, I’m not going to do maths and science, that doesn't excite me. I want to do something that excites me, so, English and drama.

“Mathematics didn't give me the same pleasure it gave Dad, and I thought you have got to do what gives you pleasure. I couldn’t see myself doing mathematics on the day I died, but maybe a Wordle? I definitely turned the page at university. I was enjoying what I was learning, I was still living at home, and Mum was okay. Everything was good.”

By the end of his university study, Michael’s mother had repartnered – her first boyfriend after Keith’s death. Michael wasn’t exactly thrilled about it. “He kept asking her to marry him, but she never did.” Then, Michael got a job at Dunedin’s Fortune Theatre, a professional theatre then, and the next phase of his life began in a career that is almost certainly different to what his dad would have envisaged for him.

“He would have wanted me to do something sciencey, for sure, and, because he was quite conservative, he would have wanted me to go for a job with good prospects – so, not theatre. And because I loved and respected him so much, I probably would have done it. Certainly, it would give me better prospects now, as an ex-TV professional! It all could have been quite different.”

But the sporadic nature of freelance TV work has allowed Michael to be the primary caregiver to his twin daughters, now in their early teens. He tries hard to find interests they have in common, to build a relationship somewhat akin to that connection he had with his dad – before he got sick. Music is a connection to one daughter (even listening patiently to Taylor Swift) and having “shot wars” at the netball hoop is to the other.

Having already outlived his father, and facing his own heart issues, Michael understands more than the most how precious that time is with his daughters.

“I had an unnerving conversation with my cardiologist recently, who reported to me that because of some ongoing issues I’ve been having I might need a heart transplant at some point. So that was a very frightening conversation. However, since then he’s said I won’t need that but still need a procedure that carries its own risks, so I’ll talk to the girls about that.”

It's a talk Michael wishes his dad had more clearly with him.

“He and I had that minute of honesty with each other at the very end, but I wish he had been more honest with me when he put that magazine cover down in front of me. That was probably his way of telling me he was going to die, but I didn’t understand. He just seemed impregnable. If there is an end that’s inevitable, be honest about it and discuss it.

“In all, I'm grateful. Dad died when he was fifty and I'm now fifty-seven. However, I really want to get more than just seven years on him, you know?”

Story by Lee-Anne Duncan